Tokyo

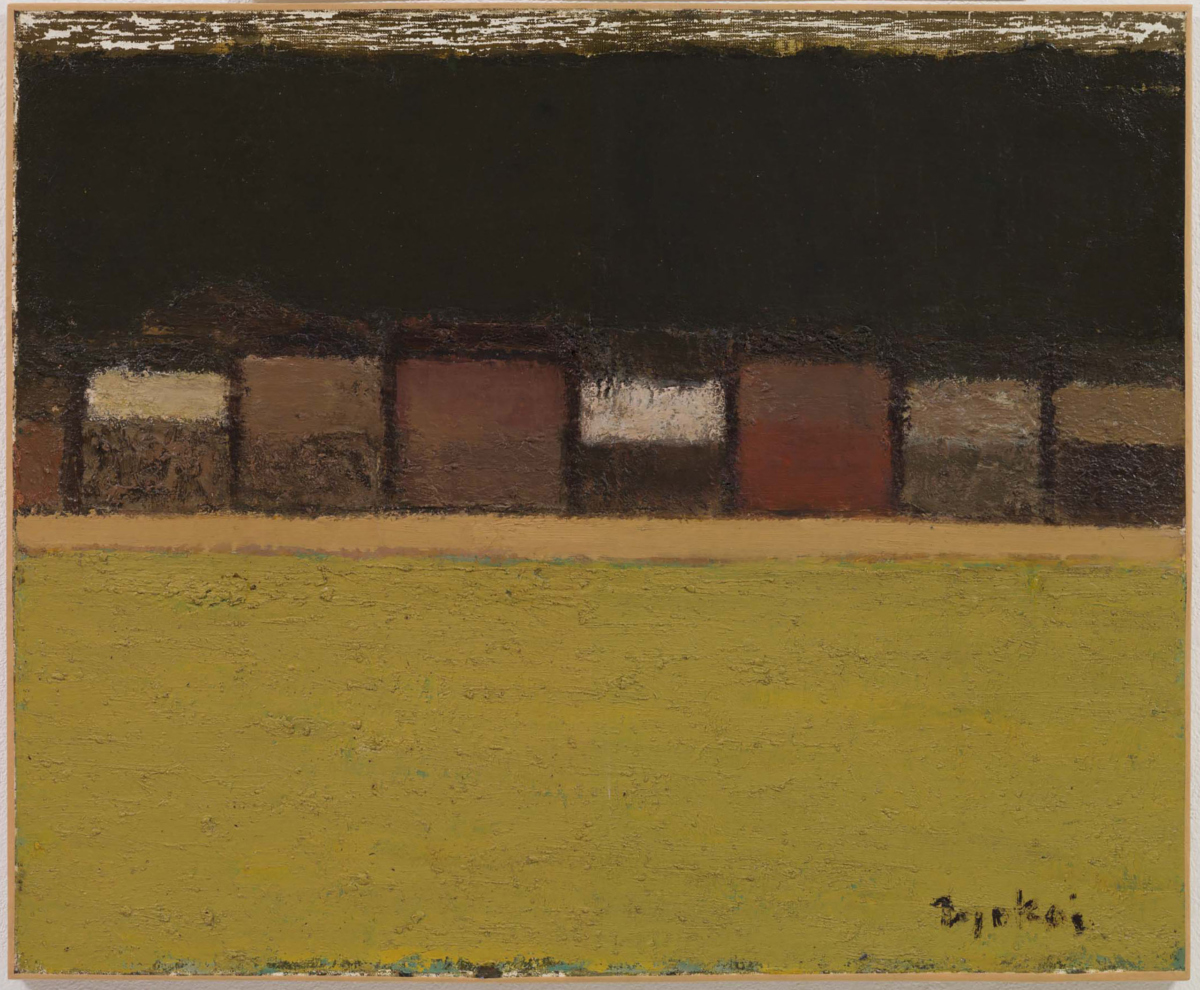

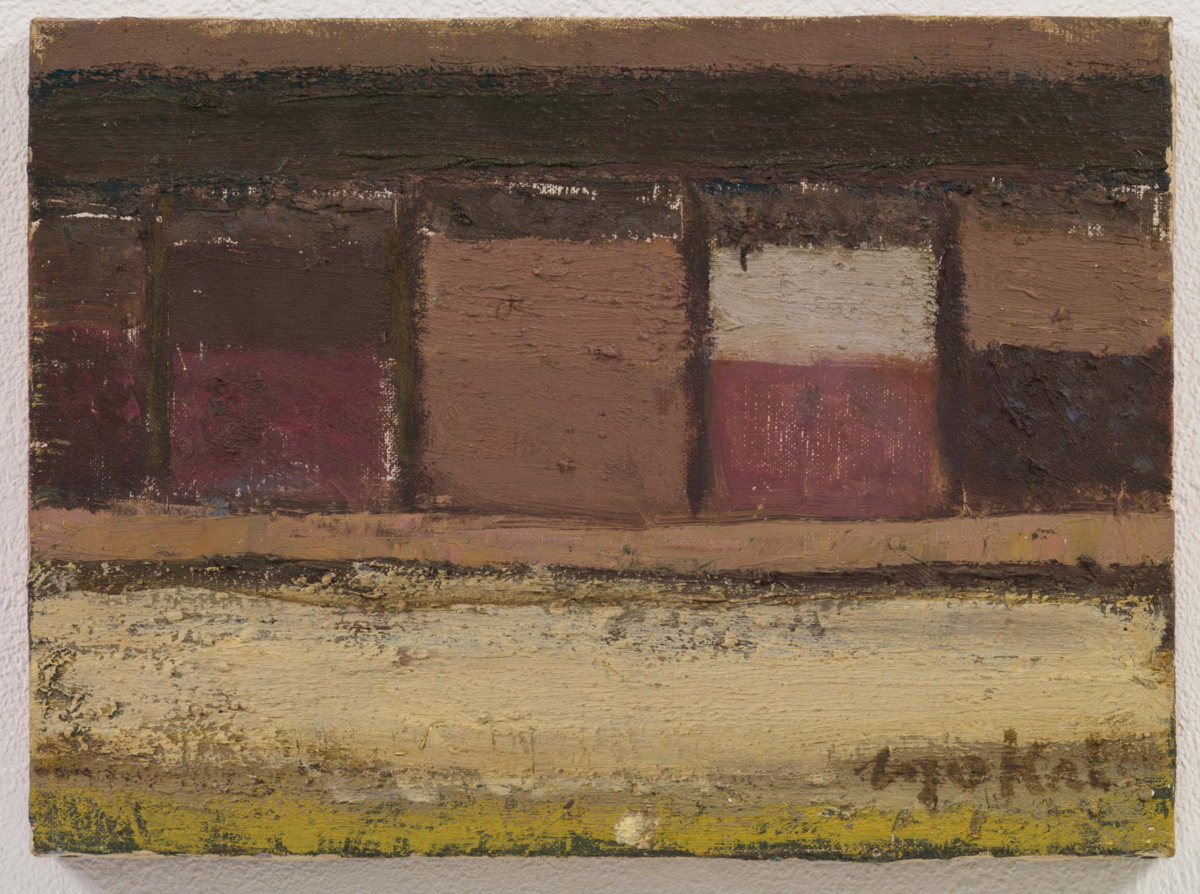

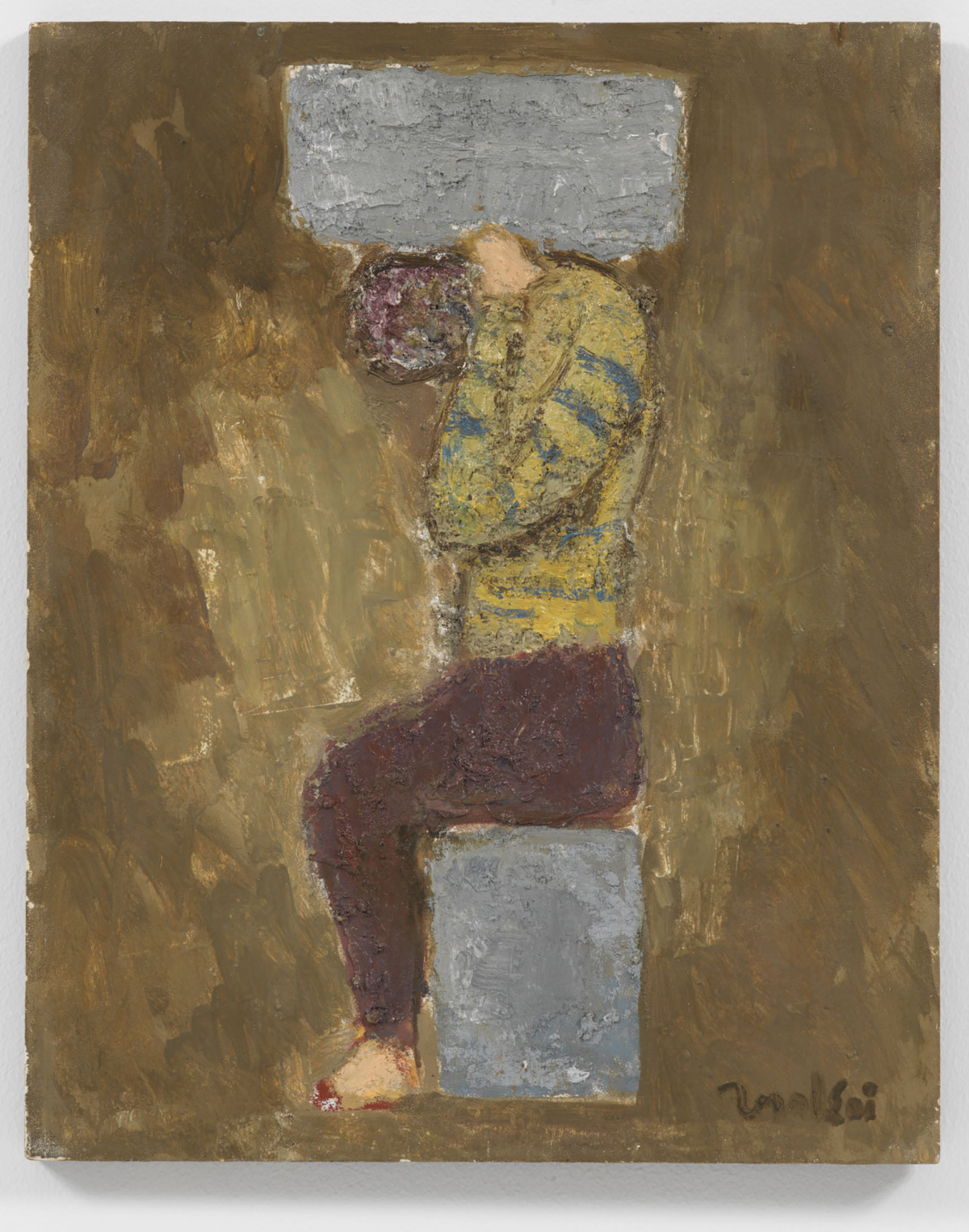

Seiji Chōkai

2017/5/13–6/24

Tokyo Gallery+BTAP is pleased to announce that our gallery is opening an exhibition of works by Seiji Chōkai.

When we opened as the Tokyo Gallery in 1951, focusing mainly on yōga (Western-style painting) and nihonga (Japanese-style painting), our inaugural exhibition featured Seiji Chōkai. Reconsidering the development of Japanese art from the founding of our gallery to the present, we decided to present another exhibition of Chōkai’s work.

Seiji Chōkai was born in Hiratsuka City, Kanagawa Prefecture, in 1902. While a student at Kansai University, he included his works in the exhibitions of the Shun-yō kai, a group of yōga painters. In 1928 he received the 6th, and in 1929, the 7th Shun-yō kai Award. In 1930 Chōkai went to Europe, where over the course of the next three years he studied the work of Western artists such as Delacroix, Goya, and Rembrandt. Under the influence of Fauvism, Chōkai began his career as a landscape painter. Later, he began to deal with various subjects, such as still life, the human figure, architecture, and historical monuments, creating works uniquely engaged with the materiality of paint. Receiving the Ministry of Education Award in 1955, the 3rd Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition Award in 1958, and the 10th Mainichi Art Award in 1959, Chōkai has continued an artistic practice that serves as a prime example of modern Japanese yōga.

After his return from Europe, Chōkai first made work with concepts and techniques derived from Western painting, but soon encountered difficulty rendering Japanese nature using oil paint. Chōkai’s solution was to focus on the possibilities of the medium and start to explore the colors and textures of paint. Now mixed with sand and stone, the painting’s surface loses its glossiness and becomes more abstract even as the paint itself carries a concrete trace of the Japanese landscape. At the same time, this material-oriented approach can also be found in contemporaneous Western painting. Chōkai’s work truly originates at the intersection of the local and the global.

It might be useless to discuss whether or not post-WWII avant-garde art in Japan was directly influenced by yōga. However, it is interesting to reconsider Chōkai’s works, with their rich exploration of materiality, in light of subsequent developments in Japanese art. Chōkai can now be appreciated as an important forerunner for artistic practices in which an incredible variety of materials for painting are sublimated into artistic expression.